Otocare at Saiseikai Kanagawaken Hospital

Research in Progress

“Otocare the first trial report”

text: Hikari Sandhu

The University of Tokyo, Institute of Industrial Science

Published on January 14th, 2021

–

–

Introduction

We live a life that is inseparable from sound.

Through our work at Memu, situated in the south of Hokkaido, we collected various nature sounds. The largely agricultural landscape of Memu is far from any significant urban areas and is surrounded by all kinds of sounds, which people comfortably live with. On the other hand, in modernised urban cities, car horns and construction noise are what we hear on a daily basis. City dwellers barely hear the sounds of the natural environment. Our sense of hearing has been compromised as we have become more accustomed to the sounds of the modern world as a result of rapid urbanisation over the decades. This in turn has led to people forgetting how to listen to nature, and how to integrate those sounds into our everyday life.

In the modern architectural field, building interiors are designed to eliminate any intrusive sounds, to apparently assist with the wellbeing and comfort of office workers, with each building setting a noise standard to create as much silence as possible. Every noise is considered an enemy to humans, with the mantra of silence is golden. However, we have to ask: Is silence natural? When we look back to our origins, we have never been in complete silence – even before we were born. We hear the flow of water and our mothers’ heartbeat in the womb. We develop our senses with human voices as we grow up. Despite these natural development stages in all of our lives, we deem the creation of silence inside buildings as a way to make them a more comfortable place.

Recent studies regarding the links between sounds and health uncovered many positive effects of naturally occurring sound on our health. The research reported the positive relationship between natural sounds and human health; some researchers reported that environmental sounds can be beneficial to people’s physical recovery from injury and disease as well as positive effects on mental health. (Hansen et al., 2017; Lee & Son, 2018). Another report showed that inaudible high-frequency sounds from nature can activate brain functions (Oohashi et al, 2000). Furthermore, the field of urban design reported that soundscape effects can increase psychological health (Hedblom et al., 2017).

With increasing interest in the relationship between sounds and health described above, we began to explore for ourselves the potential uses of nature sounds for everyday life and their impact on health, architecture, and society. The project name is OTOCARE (Sound-Care).

What we did…

The first OTOCARE goal was to deliver some of the environmental sounds from Memu, to urban cities (e.g. Tokyo, Yokohama). As we planned this experiment in the Spring of 2020, the Japanese government declared the first state of emergency in April, and many hospitals around the world reported healthcare workers’ psychological burnout including at hospitals here in Japan. With this rapidly developing situation negatively impacting many lives, we quickly moved to deliver the sounds of nature captured in Memu in the hope of easing some of the stress among healthcare workers. With generous cooperation and a welcoming, open-minded approach, we were fortunate to be able to make a collaboration with the palliative care ward[1] at Saiseikai Kanagawa-Ken Hospital, Social Welfare Organization Saiseikai Imperial Gift Foundation, Yokohama, Japan (http://www.kanagawa.saiseikai.or.jp/).

We used five types of environmental sounds for the experiment: insects sound, birds, rain sounds, human voices, and daily-life sounds (e.g. cooking, car driving, etc.). In addition to these natural sounds we worked with MSCTY (https://www.mscty.space/) and London-based ambient music producer Ski Oakenfull to create a 60 minutes mix of music and sound. (click the sound on the page) The mix was played for two weeks from June to July 2020. Twelve healthcare workers working in the ward joined this trial. After two weeks of the trial, we distributed questionnaires to the participants to ask their honest impression towards listening to this original mix of nature sound and music in the ward.

–

–

How was nature sounds to healthcare workers?

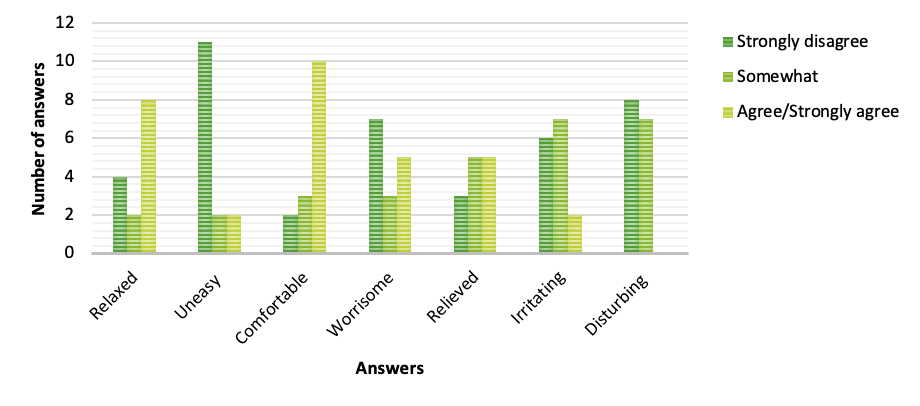

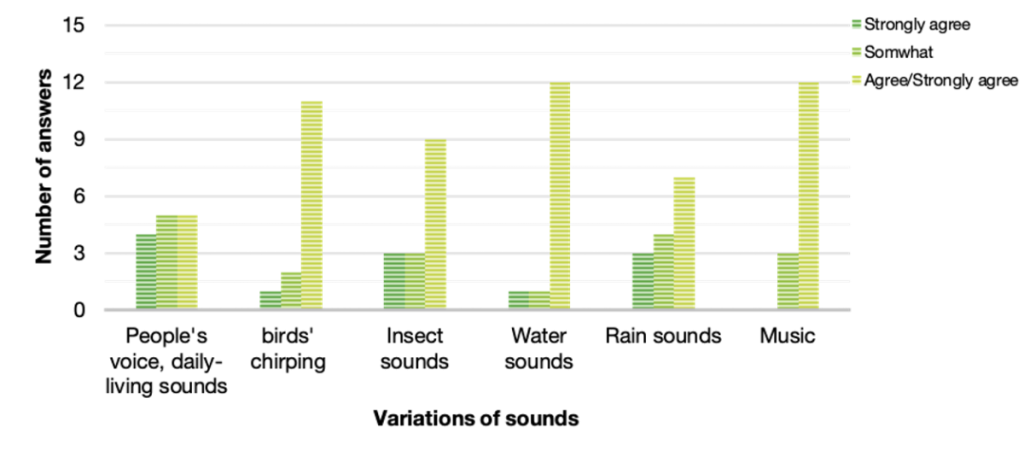

Results from the questionnaire survey showed that nature sounds eased stress among healthcare workers to some degree. Some participants reported nature sounds as relaxing and comfortable, and the nature sounds did not disturb the process of medical treatments (Figure 1). That was, the sounds were not considered as noise, rather it gave them a positive emotional experience. The participants found birds and water sounds as comfortable; on the other hand, people’s voices and daily living sounds had a less positive effect (Figure 2).

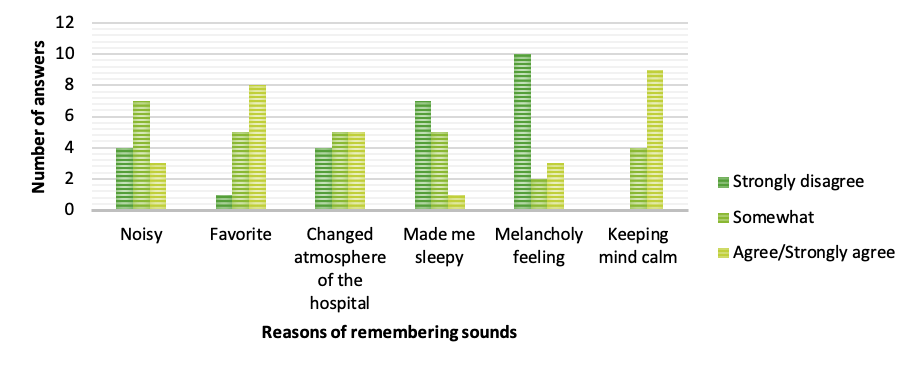

Figure 3 showed that implementing nature sounds in the hospital unit changed the atmosphere and that it somewhat created a relaxing environment. The results explain that nature sounds have a positive effect on refreshing the environment and workers’ mindset.

Figure 1: Result of question 1 “How did you feel about the sounds?”

Figure 2: Result of question 2 “Which sounds did you remember the most?”

Figure 3: Result of question 3 “Why did you remember the sound?”

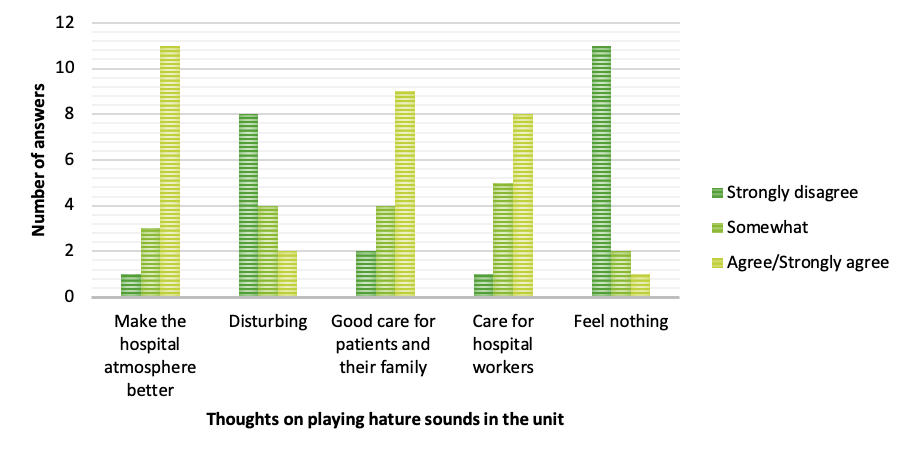

Figure 4: Result of question 4 “What do you think of playing nature sounds in the unit?”

Prospectives –

OTOCARE first trial showed that the natural sound from Menu created a positive impact on healthcare workers and the hospital unit (Figure 4). This trial leads us to new questions; what are suitable nature sounds for hospital environments? How long should we listen to the sounds to experience comfort in our environment? Our exploration of sounds and the environment also shed light on a new perspective on the architectural sound design of healthcare facilities. Although this experiment did not have a scientifically sufficient sample size, we can understand that having nature sounds in the hospital can bring a positive impact and it has opened up a new perspective in the architectural sound design field. OTOCARE will continue to explore other possibilities for and effects of nature sounds in our life.

Footnotes:

[1] The palliative care unit is a ward for terminal cancer patients, and many patients with a short life expectancy are hospitalized.

References:

Hansen, M. M., Jones, R., and Tocchini, K. (2017). Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and nature therapy: a state-of-the-art review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14 (851).

Hedblom, M., Knez, I., Ode, Sang, Å., and Gunnarsson, B. (2017). Evaluation of natural sounds in urban greenery: potential impact for urban nature preservation. Royal society of open science, 4, 170037.

Lee, H. J., Son, S. A. (2018). Qualitative assessment of experience on urban forest therapy program for preventing dementia of the elderly living alone in low-income class. Journal of people, plants, and environment, 21(6), 565-574.

Oohashi, T., Nishina, E., Honda, M., Yonekura, Y., Fuwamoto, Y., Kawai, N., Maekawa, T., Nakamura, S., Fukuyama, H., and Shibasaki, H. (2000). Inaudible high-frequency sounds affect brain activity: hypersonic effect. Journal of Neurophysiology, 83 (6).

Thank you to our partners –

Sound : Scene 1