Otocare at Shinkomoji Hospital in Kitakyushu-city

Research in Progress

“Otocare the first trial report”

text: Hikari Sandhu, Nick Luscombe, Yu Morishita

The University of Tokyo, Institute of Industrial Science

Published on July 6th, 2023

–

–

Background

Occupational health and environment

Studies of occupational health increasingly show the importance of a positive ambient environment to support workers’ health and well-being 1, 2. In their studies, several elements including gender, thermal comfort, floor planning, and environmental sounds are considered to be important elements to determine the quality of work environment experience 2. Further, research shows the environmental sounds and occupational stress have an important association; lower levels of ambient noise can boost negative job stress 3.

Hospital environment and sounds

Modern medicine is developed upon well-maintained hospital environments comprised of standardized hygiene practices and noise control, yet it lacks of perspectives on patients’ care. As guided by World Health Organization 4, hospital environments require standard principles for hygiene maintenance, which includes ventilation, spacing for each patient, quality of water, dressing of healthcare workers. As per the noise control, World Health Organization also guides noise level inside the wards as lower than 40dB during the night-time to prevent patients’ stress level 4. Followed by multiple guidelines the hospital environments created safe and inorganic spaces. Despite the environmental settings for any disease prevention for patients, ignorance of patients’ experience of hospital environment creates negative effects on patients’ and their family’s health and well-being such as anxiety, insomnia, and lack of motivation for treatment. Monti et al. show a positive effect of pictorial interventions to improve the perception of the hospital environment among pediatric patients’ family 5. The importance of positive environmental settings was clearly illustrated in previous research.

OTOCARE Project

With all background illustrated above, we conducted our first Otocare trial at Palliative care, Saiseikai Kanagawaken Hospital, in 2020 (https://memuearthlab.jp/2021/06/22/otocare-saiseikai-kanagawaken-hospital/). The result showed the potential to implement nature sounds in the hospital environment as a therapeutic use for healthcare workers. The trial was limited to a palliative care unit that focused on the calming environment as care. The first trial led us to another question: How do healthcare workers who generally work in acute medical settings react to natural environmental sounds? To answer this question, we had moved our trail location to Shinkomoji hospital in Kitakyushu-city, where had a 93.13 million population ad a 30.7 % aging rate as a comparison Yokohama city had a 372.5 million population and 24.7 % aging rate 6, 7. The research aim was to explore healthcare workers’ perception of natural sounds in acute to general medical settings.

Methods

We conducted the second trial at Shinkomoji Hospital, Kita-Kyushu city, Fukuoka Prefecture. We collaborated with a nursing department to conduct this trial. The trial period was divided into two phases: The first phase was conducted from May 26th to June 8th, 2021. We targeted a total of 353 nurses (all registered nurses in the hospital), prepared five speakers that contained 12 hours of nature sounds mixed music (Scene 1), and were allocated in 5 staff rooms in 5 hospital wards. As the intervention, participants listened to the music mix at staff rooms during their break time. After listening to the sounds, the participants filled out a questionnaire (Questionnaire A) including five questions about their daily physical and psychological status and the impact of nature sounds. After the intervention period, we distributed another questionnaire (Questionnaire B) including background, music history, and detailed questions of their sound experience and preferences of environmental sounds.

The second phase was conducted from June 16th to June 30th, 2021. We expanded the participants from nurses to multidisciplinary healthcare workers to gain wide range of insights by allocating seven speakers in seven locations. Locations included a general medicine staff room, a surgical department staff room, an outpatient treatment room, a nurse station, a community care room, and an outpatient consultation room. As the intervention, participants listened to the music mix at each location during their break time. After the intervention period, we distributed Questionnaire B as the first phase, which included participants’ background, music history, and detailed questions of their sound experience and preferences of environmental sounds.

–

Findings

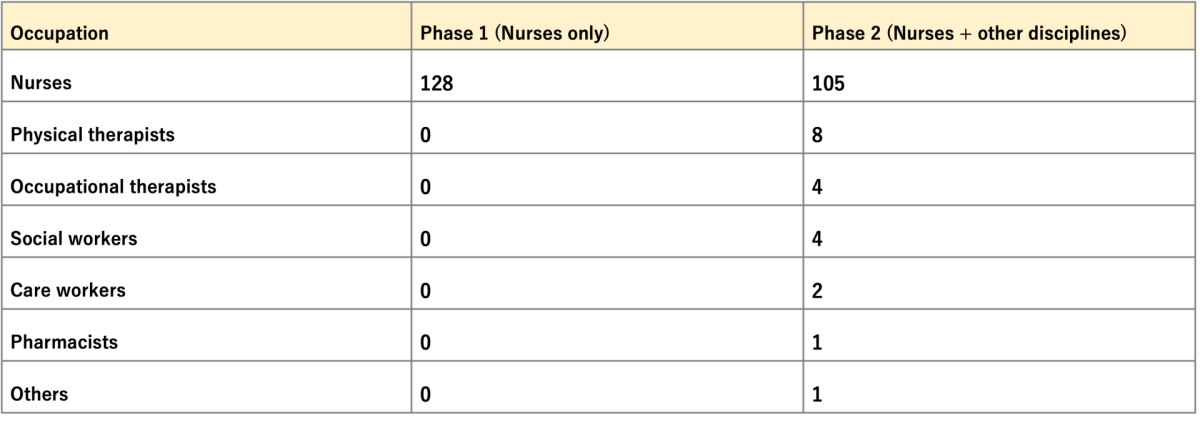

We collected 128 responses for Questionnaire A and 76 responses for Questionnaire B for the first phase, and 125 responses for questionnaire B in the second phase. Table 1 showed the details of participants:

Table 1: Participants details

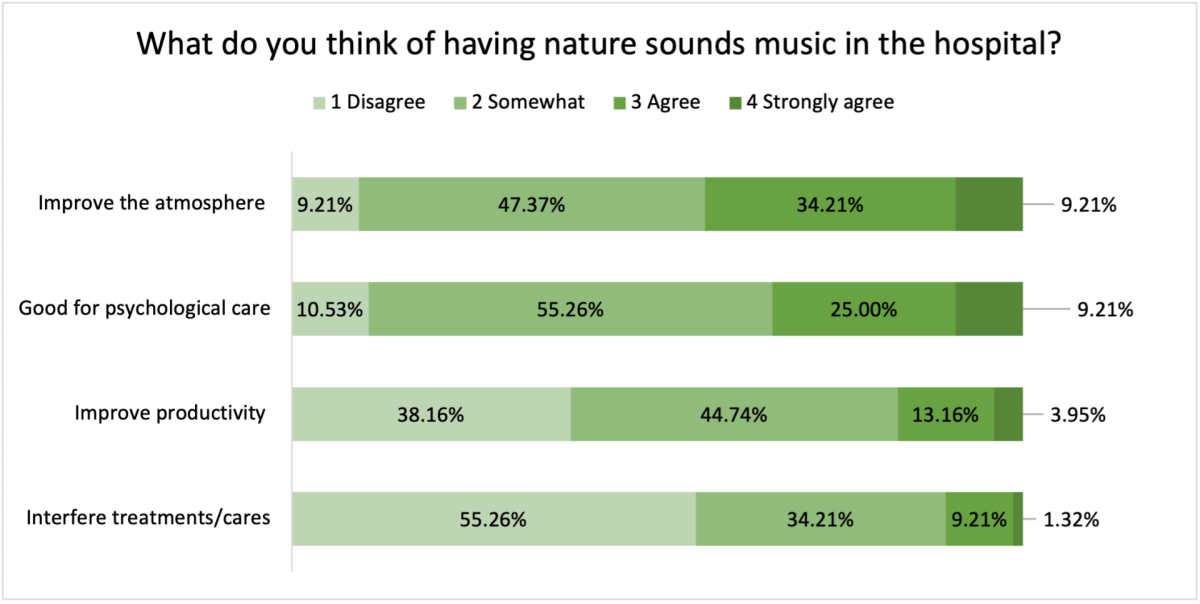

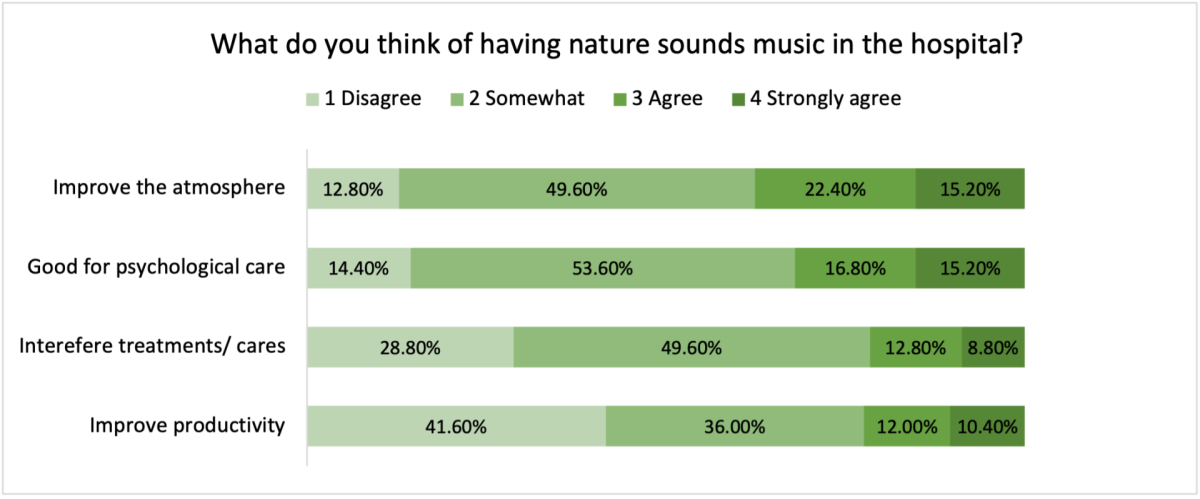

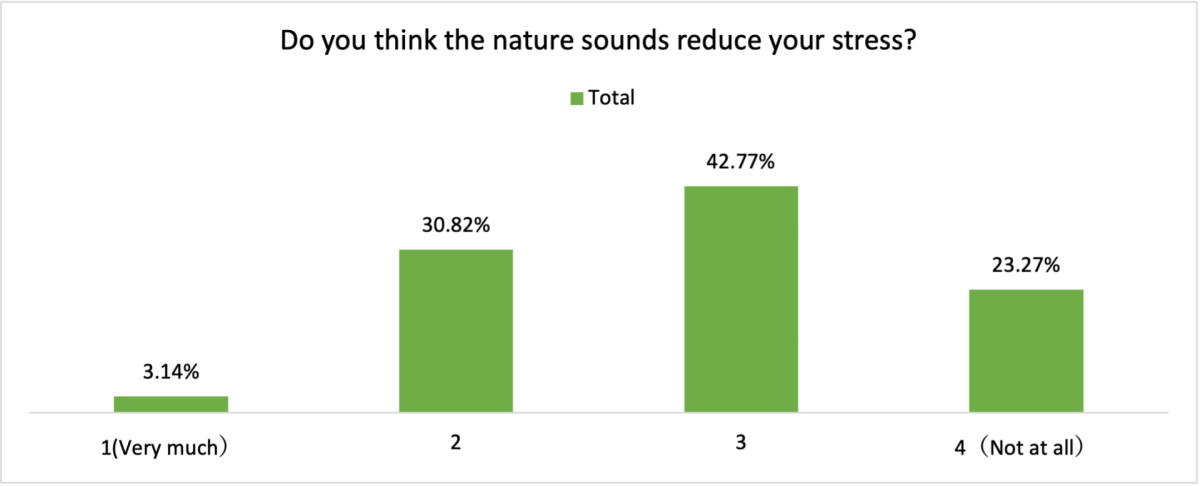

The results showed three main findings. The first finding presented listening to nature sounds music can enhance relaxation among nurses, yet it may not directly reduce stressors. Diagram 1 showed the results from nurses during the first phase, and diagram 2 showed the results of the second phase from multidiscipline, including nurses and other occupations. Both diagrams showed that over 70 % of respondents answered positively to having nature sounds music in the hospital; in contrast, diagram 3 showed that the nature sounds did not reduce stress reduction daily. That is, natures sounds based music may not be enough to induce strong stress reduction but can provide a temporary relaxed experience.

Diagram 1: Subjective impact of nature sounds in the hospital environment from Nurses

Diagram 2: Subjective impact of nature sounds in the hospital environment from Nurses + other disciplines

Diagram 3: Subjective evaluation of nurses’ daily stress reduction by nature sounds

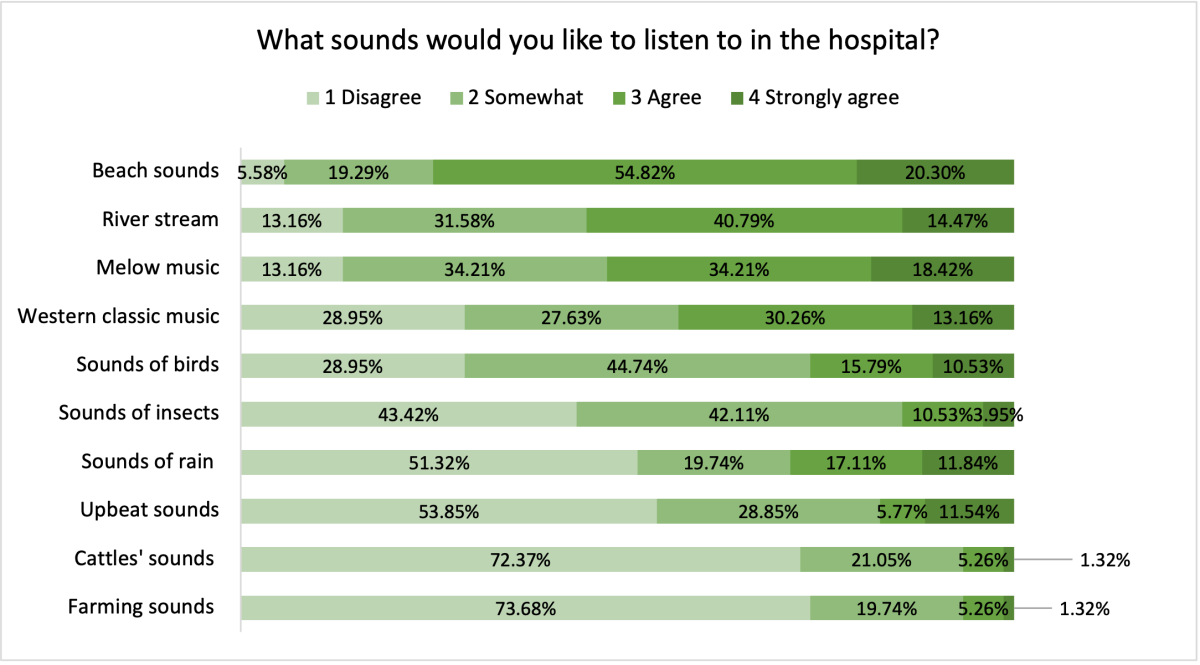

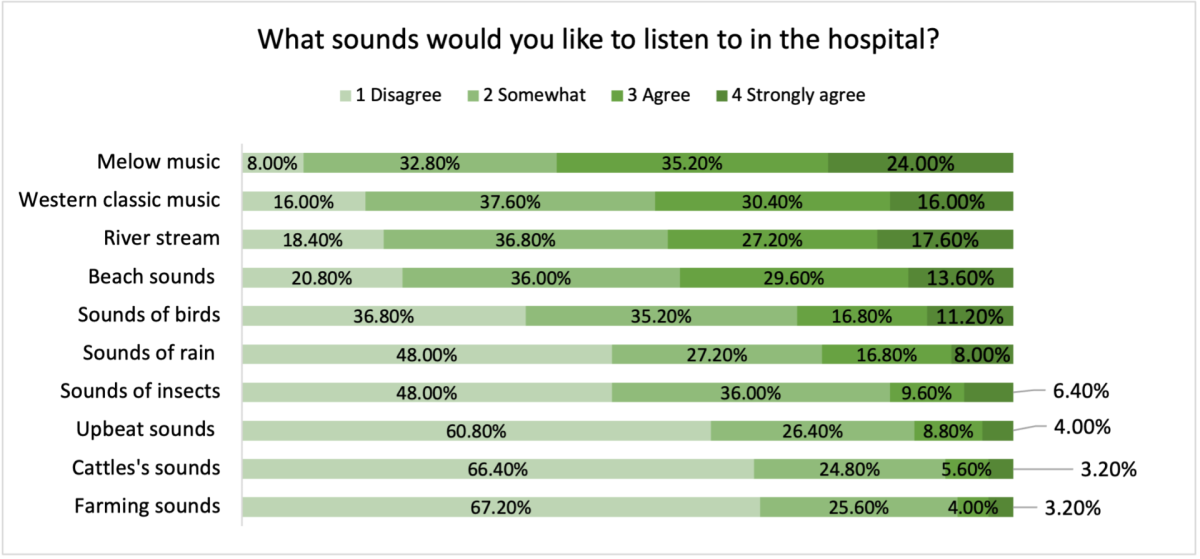

The second finding showed that the sound of the river, western classical music, and slow tempo music is preferred (diagram 4 and diagram 5). Among all nature sounds, river sounds or beach sounds contain mono-toned continuous sounds compared to other sounds such as birds or rain sounds containing changeable irregular sounds. The mono-toned continuous sounds may contribute to stabilizing the environmental sounds and the atmosphere created by the sounds. As for the preference for western classical music and slow tempo music, both sounds have more familiarity as the hospital usually plays mellow musical box sounds as background music. This familiarity leads to a preference of sounds and music.

Diagram 4: Preferred sounds to listen to in the hospital (Nurses)

Diagram 5: Preferred sounds to listen to in the hospital (Nurses + other disciplines)

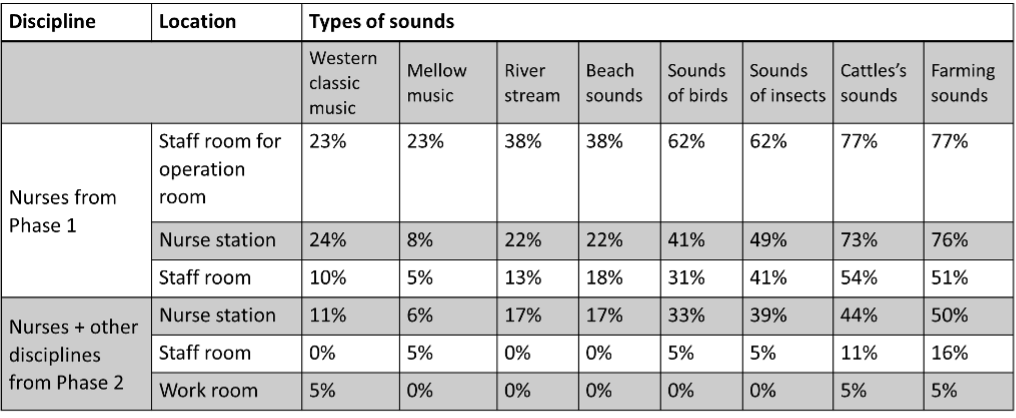

Finally, the third finding showed that participants perceive sounds differently depending on their locations and circumstances. We allocated speakers in seven different locations as a total. Results showed that participants who listened to the sounds at a surgical department staff room had a different perception of sounds than participants in different locations. The high-intensity workplaces may need to maintain tension to keep high-quality work and productivity, which relaxational sounds, including nature sounds, may not be suitable.

Table 2: Comparison of ‘Disagree’ responses from survey data

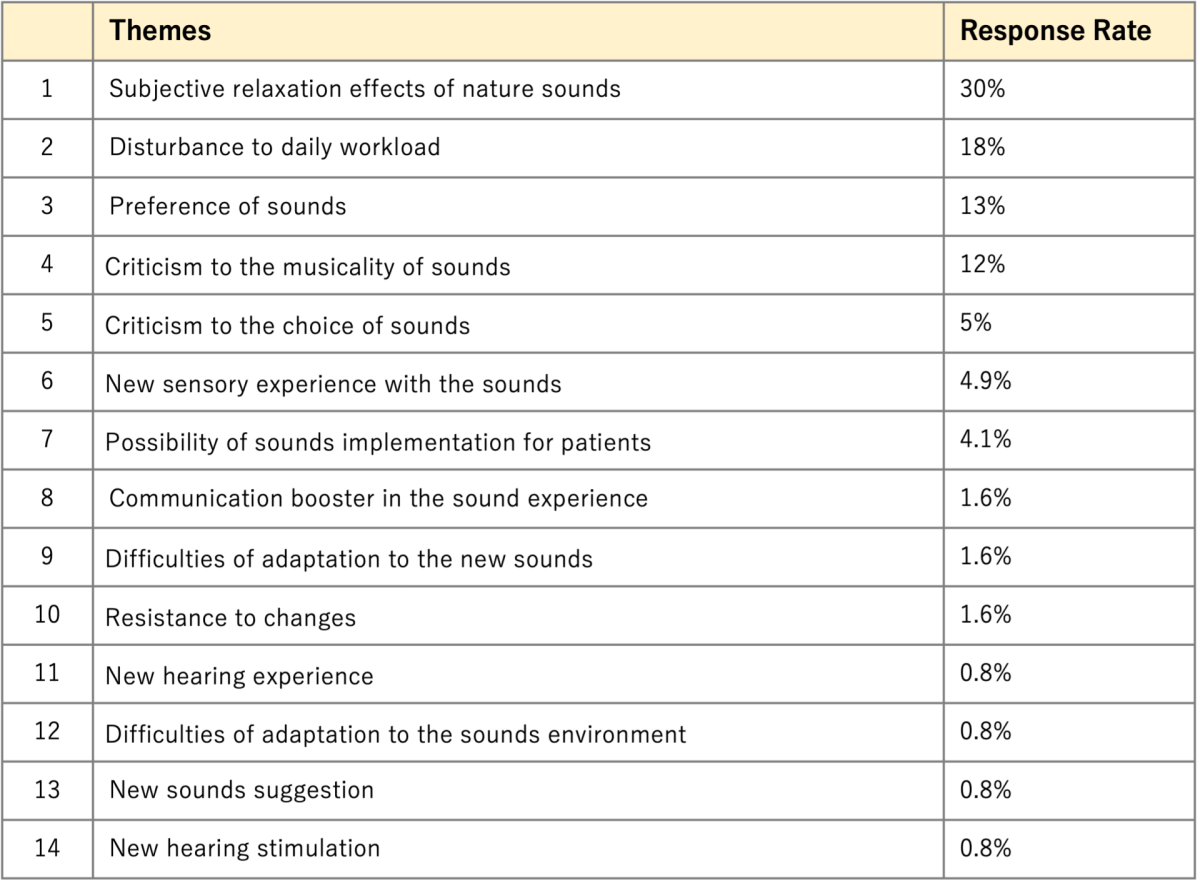

Appendix 1: Thematic analysis from written interviews

Perspectives-

Otocare second trial showed that nature sounds could reduce stress among healthcare workers who work in acute to general medical fields. Further, we explored river sounds or beach sounds were more preferred sounds compare to other nature sounds. Importantly we were able to collect over 100 responses that had a scientifically sufficient sample size. Consequently, Otocare trials suggest to increase implementation of nature sounds into healthcare fields as a part of psychological care for healthcare workers. To drive forward this care, we need to explore implementation methods suitable for the healthcare environment, such as allocations, sound management systems, device choices, and the sustainability of entire systems. Otocare will continue to investigate such points in collaboration with architectures, sound system engineers.

References

- Gatti, M.F.Z. & Silva, M.J.P. (2007). Ambient music in the emergency services: the professionals’ perception. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem, maio-junho; 15(3):377-83.

- Mulville, M., Callaghan, N. & Isaac, D. (2016) “The impact of the ambient environment and building configuration on occupant productivity in open-plan commercial offices”, Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 18(3), pp.180-193.

- Leather, P., Beale, D. & Sullivan, L. (2003). Noise, psychosocial stress and their interaction in the workplace. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23, p.213-222.

- Berglund, B., Lindvall, T., Schwela, D.H .& World Health Organization. (1996). Occupational and Environmental Health Team. Guidelines for Community Noise. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66217

- Monti, F., Agostini, F., Dellabartola, S., Neri, E., Bozicevic, L, & Pocecco, M. (2012). Pictorial intervention in a pediatric hospital environment: effects on parental affective perception of the unit. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32, p.216-224. et al. (2012)

- City of Kitakyushu (2022. Retrieved from https://www.city.kitakyushu.lg.jp/soumu/file_0311.html

- City of Yokohama (2023). Retrieved from https://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/city-info/yokohamashi/tokei-chosa/portal/jinko/maitsuki/saishin-news.html

Thank you to our partners –

Sound : Scene 1